Fundamentals encompass natural and man-made materials like stone, timber, brick, and glass, alongside crucial techniques for foundations, walls, and structural elements.

Historical Overview of Building Materials

Throughout history, building materials have mirrored societal advancements and resource availability. Early civilizations heavily relied on natural materials – stone for monumental structures, timber for readily available framing, and earth-based materials like mud for simpler dwellings. These choices were dictated by local geology and climate.

The advent of brick-making marked a significant shift towards man-made materials, offering greater consistency and durability. Later, the Romans revolutionized construction with their mastery of concrete, enabling large-scale infrastructure projects. The industrial revolution brought forth cement production, further expanding concrete’s applications.

Modern times witness the rise of glass and plastics, offering unique properties and design possibilities. Today, a growing emphasis on sustainability drives the exploration of reclaimed materials and innovative, eco-friendly alternatives, echoing a return to appreciating the fundamentals of resourcefulness and longevity in building practices.

Classification of Building Materials

Building materials are broadly categorized into two primary groups: natural and man-made. Natural materials, sourced directly from the earth, encompass stone – granite, limestone, sandstone – and timber, offering inherent aesthetic qualities and varying structural properties. Earth-based materials, like mud and clay, represent another significant natural category, particularly in vernacular architecture.

Man-made materials are products of industrial processes, transforming raw resources into usable building components. This category includes bricks and tiles, manufactured through firing clay, and cement-based materials like concrete, offering exceptional strength and versatility. Glass, produced from silica, and plastics/composites, engineered for specific performance characteristics, also fall under this classification.

Further categorization considers material properties – structural (load-bearing), thermal (insulation), and aesthetic (finishes). Understanding these classifications is fundamental for selecting appropriate materials based on project requirements and performance goals.

Natural Building Materials

Natural resources, such as stone, timber, and earth, have been foundational to construction for millennia, offering sustainable and readily available options.

Stone as a Building Material

Stone represents one of humanity’s oldest building materials, prized for its durability, strength, and aesthetic appeal. Throughout history, civilizations have utilized locally sourced stone for constructing monumental structures and everyday dwellings. Its inherent compressive strength makes it ideal for foundations, walls, and pavements.

Different geological formations yield various stone types, each possessing unique characteristics. The selection of stone depends on factors like availability, cost, and the specific structural requirements of the project. Stone’s longevity contributes to sustainable building practices, reducing the need for frequent replacements. However, quarrying and transportation can have environmental impacts, necessitating responsible sourcing.

Modern techniques, alongside traditional masonry, continue to employ stone in innovative ways, blending historical craftsmanship with contemporary design. Stone remains a testament to enduring building principles.

Types of Stone Used in Construction

Granite, an igneous rock, offers exceptional hardness and resistance to weathering, making it suitable for demanding applications like paving and structural elements. Limestone, a sedimentary rock, is relatively softer and easier to work with, commonly used for facades and decorative features. Sandstone, another sedimentary option, provides a warm aesthetic and good durability for walling.

Slate, a metamorphic rock, is known for its distinct layering and impermeability, ideal for roofing and flooring. Marble, also metamorphic, is prized for its beauty and polish, often used for interior finishes and monuments. The choice depends on project needs.

Each stone type exhibits varying compressive strength, porosity, and aesthetic qualities, influencing its suitability for specific building components. Proper selection ensures structural integrity and long-term performance.

Timber: Properties and Applications

Timber, a renewable resource, boasts a high strength-to-weight ratio, making it ideal for framing, roofing, and flooring. Its natural insulation properties contribute to energy efficiency. Different wood species exhibit varying densities and strengths; softwoods like pine and fir are easier to work with, while hardwoods such as oak and maple offer greater durability.

Timber’s applications range from structural components like beams and columns to aesthetic elements like cladding and finishes. Proper treatment is crucial to protect against decay, insects, and fire. Modern engineered wood products, like plywood and laminated veneer lumber (LVL), enhance strength and dimensional stability.

Sustainable sourcing and utilizing reclaimed wood are increasingly important for environmentally responsible construction.

Sustainable Timber Sourcing and Reclaimed Wood

Sustainable timber sourcing prioritizes forests managed for long-term health and biodiversity, often certified by organizations like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). This ensures responsible harvesting practices, minimizing environmental impact and supporting local communities. Choosing sustainably sourced timber reduces deforestation and promotes carbon sequestration.

Reclaimed wood, salvaged from old buildings, barns, or industrial structures, offers a unique aesthetic and significantly reduces demand for newly harvested timber. It embodies circular economy principles, diverting waste from landfills and preserving embodied energy. Reclaimed timber often possesses superior strength and character due to its age and previous use.

Harnessing reclaimed timber is a valuable way to achieve sustainability goals within the construction sector, offering both environmental and economic benefits.

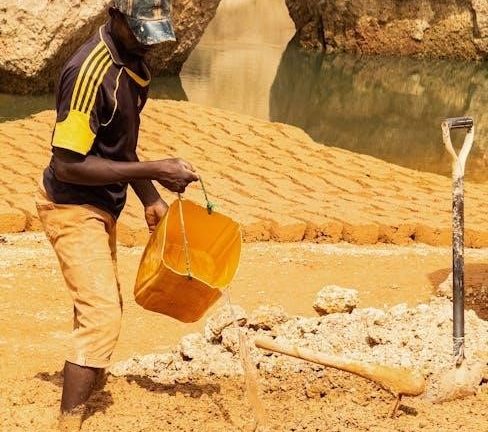

Mud and Earth-Based Construction

Mud and earth-based construction represents one of humanity’s oldest building techniques, utilizing readily available natural resources. These methods encompass various approaches, including cob, adobe, rammed earth, and wattle and daub, each differing in composition and construction process. Historically, these techniques provided affordable and thermally efficient housing in diverse climates.

Adobe utilizes sun-dried earth bricks, while rammed earth compacts damp earth within forms to create dense, durable walls. Cob involves sculpting a mixture of clay, sand, and straw directly into walls. These methods offer excellent thermal mass, regulating indoor temperatures and reducing energy consumption.

Modern adaptations are exploring stabilized earth techniques, incorporating materials like cement or lime to enhance strength and durability, making earth construction a viable sustainable option.

Man-Made Building Materials

Man-made materials, like bricks, cement, concrete, glass, and plastics, are engineered for specific properties, offering versatility and enabling modern construction techniques.

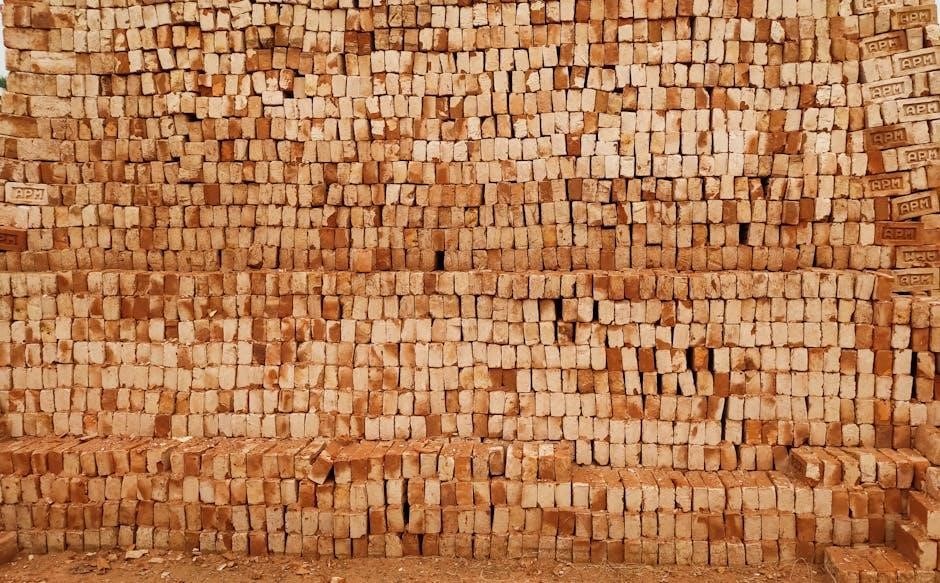

Bricks and Tiles: Manufacturing and Uses

Bricks and tiles represent fundamental components in construction, produced through diverse manufacturing processes involving clay, shale, or concrete mixtures. The process typically includes material preparation, molding – utilizing methods like extrusion or pressing – drying, and finally, firing in kilns to achieve durability and strength.

Their applications are incredibly broad, ranging from load-bearing walls and pavements to decorative facades and roofing. Different types, such as common burnt clay bricks, engineering bricks (renowned for high strength), and glazed tiles, cater to specific structural and aesthetic requirements.

The selection depends on factors like compressive strength, water absorption, and resistance to weathering. Modern advancements include the production of lightweight bricks and tiles, contributing to reduced structural loads and improved thermal insulation. These materials continue to be vital due to their cost-effectiveness, availability, and versatility in various building projects.

Cement and Concrete: Composition and Properties

Cement, typically Portland cement, acts as the crucial binding agent in concrete, a composite material formed by mixing cement with aggregates (sand, gravel, or crushed stone) and water. The chemical reaction, hydration, hardens the mixture, creating a robust and durable material. Concrete’s properties – compressive strength, tensile strength (though low), durability, and workability – are fundamental to its widespread use.

Different cement types cater to specific needs, like rapid hardening or sulfate resistance. Aggregate size and grading significantly influence concrete’s workability and strength. Admixtures are often added to modify properties, enhancing workability, accelerating or retarding setting time, or improving durability.

Concrete’s versatility allows for diverse applications, from foundations and structural frames to pavements and dams. Ongoing research focuses on sustainable concrete mixes, incorporating recycled materials and reducing cement content to minimize environmental impact.

Concrete Mix Design and Sustainability

Concrete mix design is a meticulous process determining the optimal proportions of cement, aggregates, water, and admixtures to achieve desired strength, workability, and durability. Factors considered include intended use, environmental exposure, and cost-effectiveness. Achieving the right balance is crucial for structural integrity and longevity.

Sustainability in concrete production focuses on reducing its carbon footprint. Utilizing supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) like fly ash and slag – combustion residuals – partially replaces Portland cement, lowering CO2 emissions. Recycled aggregates, sourced from construction and demolition waste, further enhance sustainability.

Innovative approaches include carbon capture and utilization technologies, and developing self-healing concrete. These advancements aim to create a more environmentally responsible construction material, aligning with global sustainability goals and reducing the industry’s environmental impact.

Glass in Modern Construction

Glass has evolved from a simple glazing material to a versatile component in modern building design, offering aesthetic appeal and functional benefits. Its excellent combination of physical and chemical properties – transparency, strength, and resistance to corrosion – makes it ideal for diverse applications.

Beyond windows, glass is utilized in curtain walls, facades, skylights, and interior partitions, maximizing natural light and creating open, airy spaces. Advanced glass technologies, like low-emissivity (low-E) coatings and laminated safety glass, enhance energy efficiency and structural performance.

Furthermore, specialized glass types, such as self-cleaning and smart glass, offer additional functionalities. The increasing demand for sustainable buildings drives innovation in glass manufacturing, focusing on recycled content and reduced energy consumption during production.

Plastics and Composites in Building

Plastics and composite materials are increasingly prevalent in construction, offering lightweight alternatives to traditional materials with unique properties. These materials encompass a broad range, including PVC, polyethylene, and fiber-reinforced polymers (FRPs).

Their applications span diverse areas, such as piping, insulation, roofing, cladding, and structural components. Composites, combining a matrix (like resin) with reinforcement (like fibers), exhibit high strength-to-weight ratios and corrosion resistance, making them suitable for demanding environments.

However, concerns regarding durability, fire resistance, and recyclability necessitate careful material selection and design considerations. Ongoing research focuses on developing bio-based plastics and improving the sustainability of composite manufacturing processes, addressing environmental impacts.

Building Construction Methods

Methods involve foundation techniques, diverse wall construction approaches – including masonry – and erecting essential structural elements like columns and robust beams.

Foundation Construction Techniques

Foundation construction represents a critical initial phase, demanding careful consideration of soil conditions and structural loads. Several techniques exist, each suited to specific site characteristics and building requirements. Shallow foundations, like spread footings, are economical for stable soils with minimal load. Conversely, deep foundations – including piles and caissons – become necessary when encountering weak or unstable ground.

Pile foundations transfer loads to deeper, stronger soil strata, while caissons involve constructing watertight structures and excavating to the desired depth. Proper soil investigation, including bearing capacity analysis, is paramount. Effective drainage systems are also crucial to prevent hydrostatic pressure build-up and potential foundation damage. The selection of appropriate materials, like concrete and reinforcing steel, ensures long-term stability and durability. Modern advancements incorporate ground improvement techniques to enhance soil properties before foundation construction begins.

Wall Construction Methods

Wall construction employs diverse methods, dictated by material availability, structural needs, and aesthetic preferences. Masonry, utilizing bricks, stones, or concrete blocks, remains a prevalent choice, offering durability and thermal mass. Framed construction, employing timber or steel studs, provides flexibility and speed of erection, often infilled with insulation and cladding.

Concrete walls, cast-in-place or precast, deliver exceptional strength and fire resistance. Emerging techniques include insulated concrete forms (ICFs), offering energy efficiency and simplified construction. Proper detailing is vital to ensure weather tightness, structural integrity, and effective insulation. Considerations include load-bearing capacity, resistance to lateral forces, and compliance with building codes. The choice of method significantly impacts construction timelines, costs, and the overall building performance.

Masonry Techniques

Masonry techniques involve assembling bricks, stones, or concrete blocks using a mortar binder. Common bonds, like stretcher, English, and Flemish, dictate the arrangement of units for structural stability and aesthetic appeal. Proper mortar mixing and application are crucial for bond strength and weather resistance. Laying involves careful alignment, leveling, and jointing to create a plumb and even wall.

Reinforced masonry incorporates steel reinforcement to enhance tensile strength and seismic resistance. Veneer masonry provides a decorative facing applied to a structural frame. Skilled craftsmanship is essential for achieving durable and visually appealing results. Considerations include material compatibility, expansion and contraction, and detailing around openings. Effective flashing and weep holes prevent water penetration, ensuring long-term performance and preventing structural damage.

Structural Elements: Columns and Beams

Columns and beams are fundamental load-bearing elements in building construction. Columns primarily resist compressive forces, transferring loads vertically to foundations. Materials include concrete, steel, and timber, each with varying strengths and applications. Beams resist bending moments and shear forces, spanning openings and supporting floors or roofs. Their design considers span length, load magnitude, and material properties.

Concrete beams often utilize steel reinforcement to enhance tensile strength, creating reinforced concrete. Steel beams offer high strength-to-weight ratios, suitable for long spans. Timber beams provide a sustainable option, particularly in residential construction. Proper connections between columns and beams are critical for structural integrity, employing techniques like bolting, welding, or cast-in-place concrete.

Sustainable Building Practices

Practices involve utilizing combustion residuals, promoting vertical construction for urban density, and integrating sustainability into construction TVET curricula for a greener future.

Application of Combustion Residuals in Ceramic Materials

The construction industry is actively seeking sustainable alternatives, and the utilization of hard coal combustion residuals presents a promising avenue for eco-friendly ceramic building material production. Research, such as documented in Construction and Building Materials (Vol. 304, 124506, 2021, authored by E.V. Kartseva), demonstrates the feasibility of incorporating these residuals.

This approach addresses waste management challenges while simultaneously reducing the environmental impact associated with traditional ceramic manufacturing. By repurposing these byproducts, the demand for virgin raw materials decreases, conserving natural resources and lowering carbon emissions. The application requires careful consideration of the residual’s chemical composition and physical properties to ensure the resulting ceramic materials meet required performance standards. Further investigation into optimal mixing ratios and processing techniques is crucial for widespread adoption and maximizing the benefits of this sustainable practice.

Vertical Construction and Urban Density

As global populations concentrate in urban centers, the necessity for innovative building strategies becomes paramount. With projections indicating over 6 billion city dwellers by 2050, expanding outwards is often impractical, necessitating a shift towards vertical construction. This approach maximizes land utilization and accommodates growing density within existing urban footprints.

Effective implementation of vertical construction relies heavily on advancements in building materials and construction methods. High-strength concrete, steel frameworks, and efficient facade systems are essential for creating safe, stable, and sustainable high-rise structures. Furthermore, careful planning and logistical coordination are vital to manage the complexities of building upwards, ensuring efficient material transport and on-site operations. This trend directly impacts the demand for specialized construction skills and technologies, driving innovation within the industry.

Integrating Sustainability into Construction TVET Curriculum

Modern Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) programs in construction must prioritize sustainability as a core principle. This integration extends beyond simply selecting eco-friendly building materials; it encompasses a holistic approach to responsible construction practices. Curriculum should address the entire lifecycle of buildings, from material sourcing and energy efficiency to waste reduction and responsible demolition.

Crucially, sustainability education should also incorporate social considerations, including gender equality within the construction workforce and upholding workers’ rights to organize. Training should equip students with the knowledge to assess the environmental impact of different materials and methods, promoting informed decision-making. Ultimately, a sustainable construction TVET curriculum prepares a workforce capable of building a more resilient and environmentally conscious future.